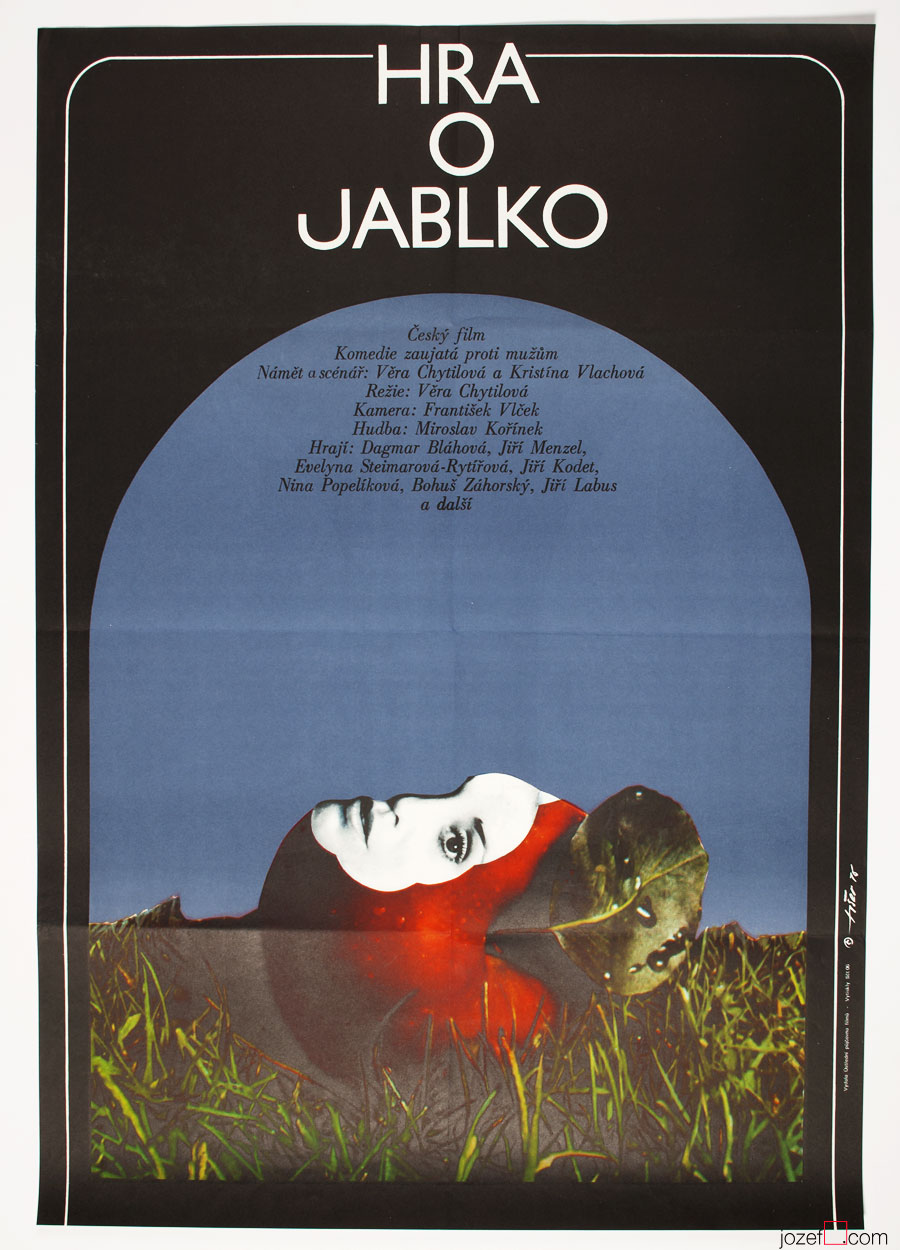

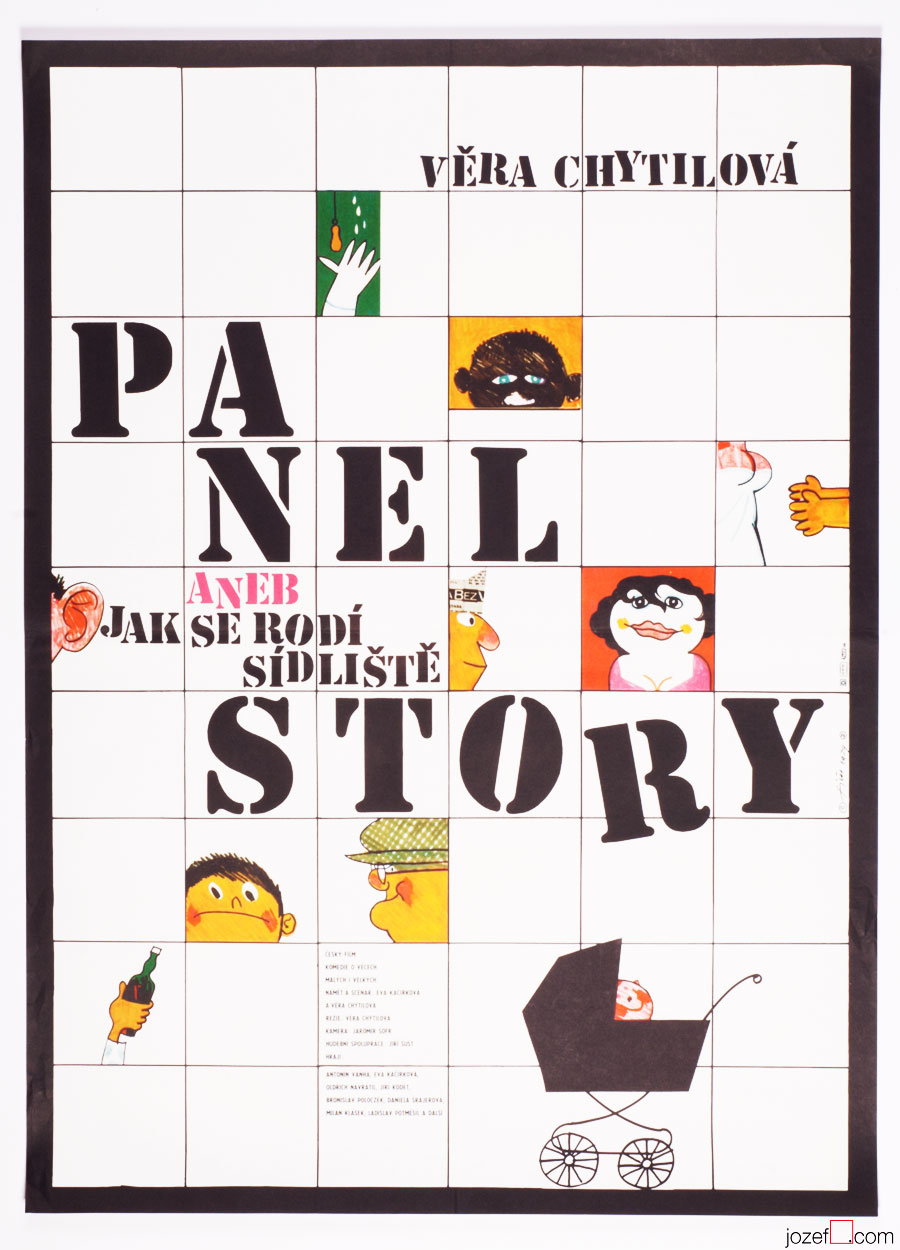

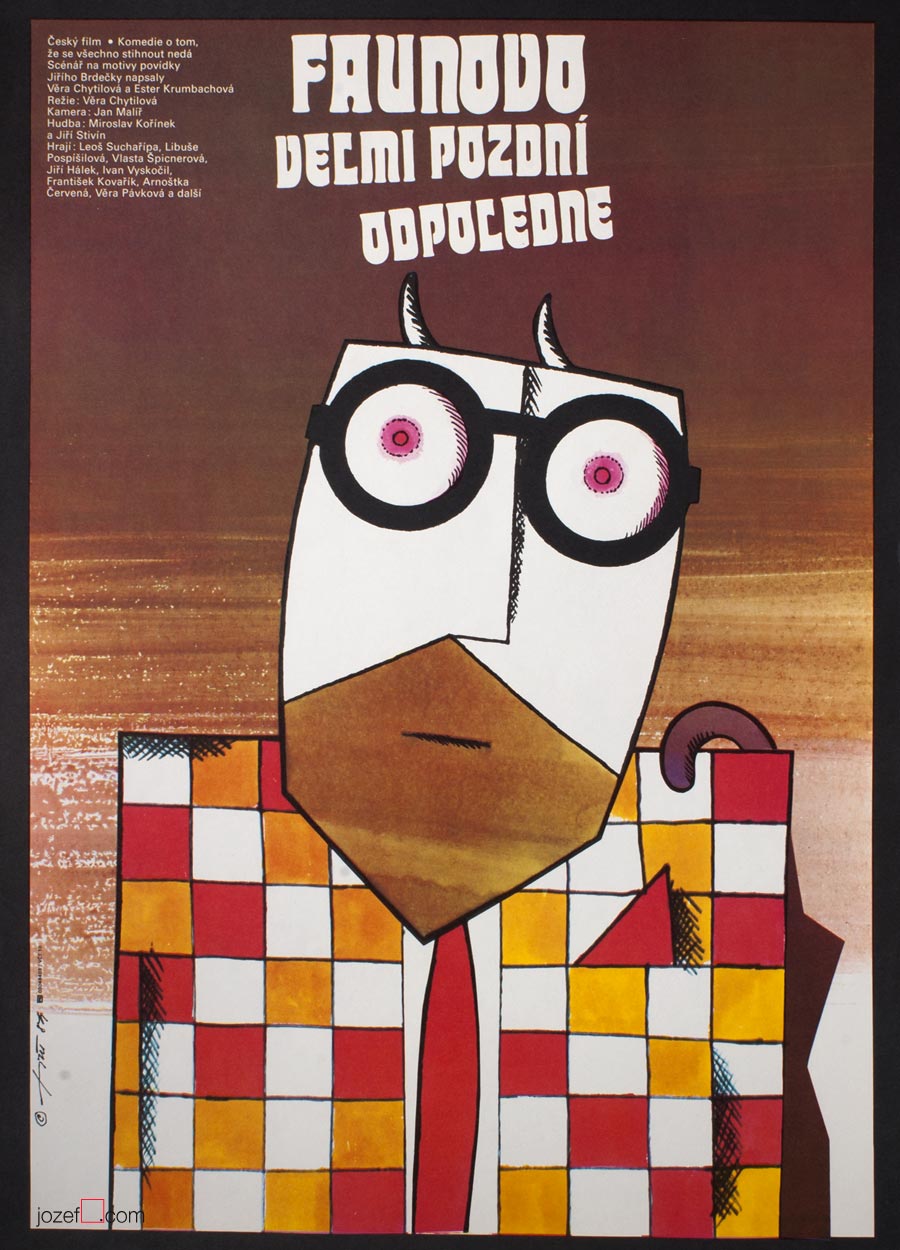

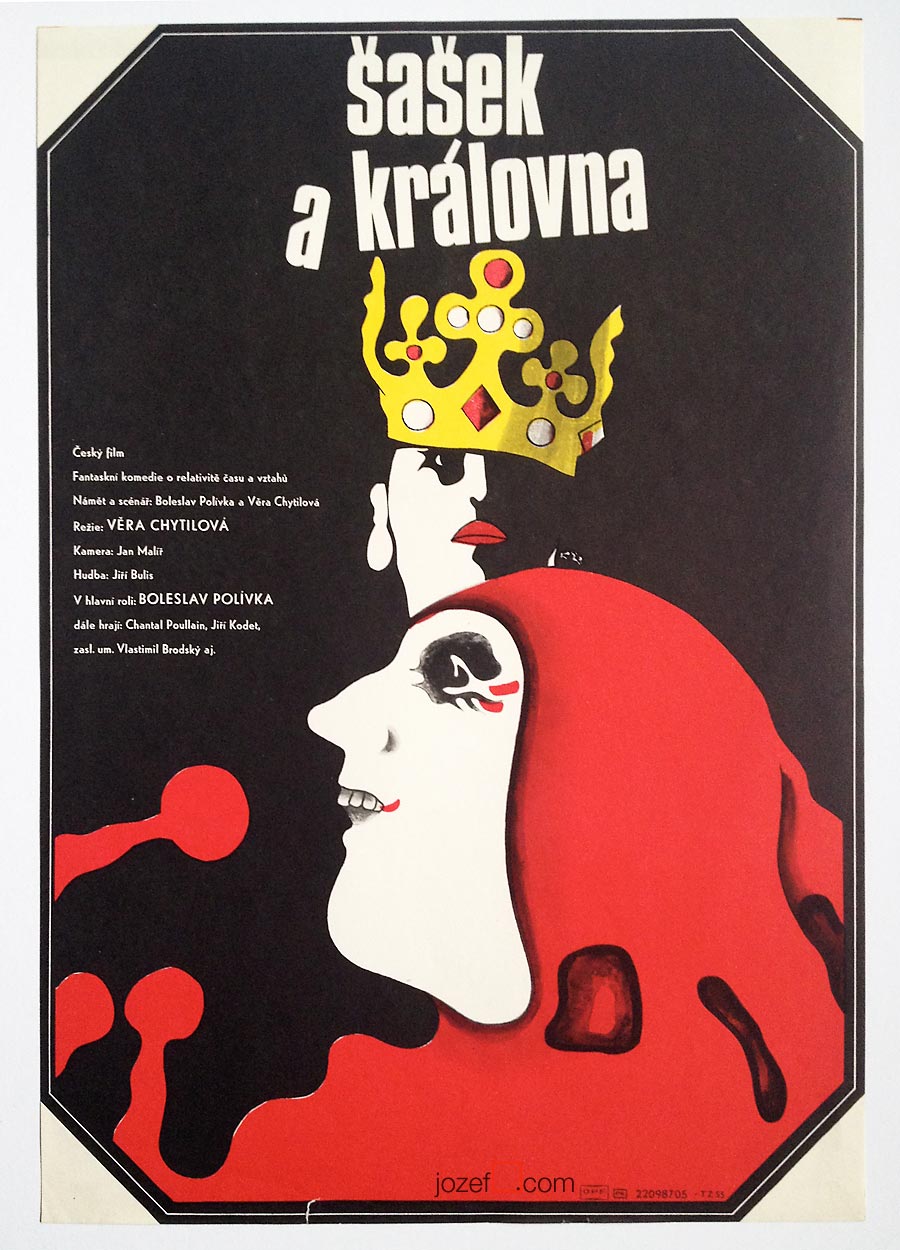

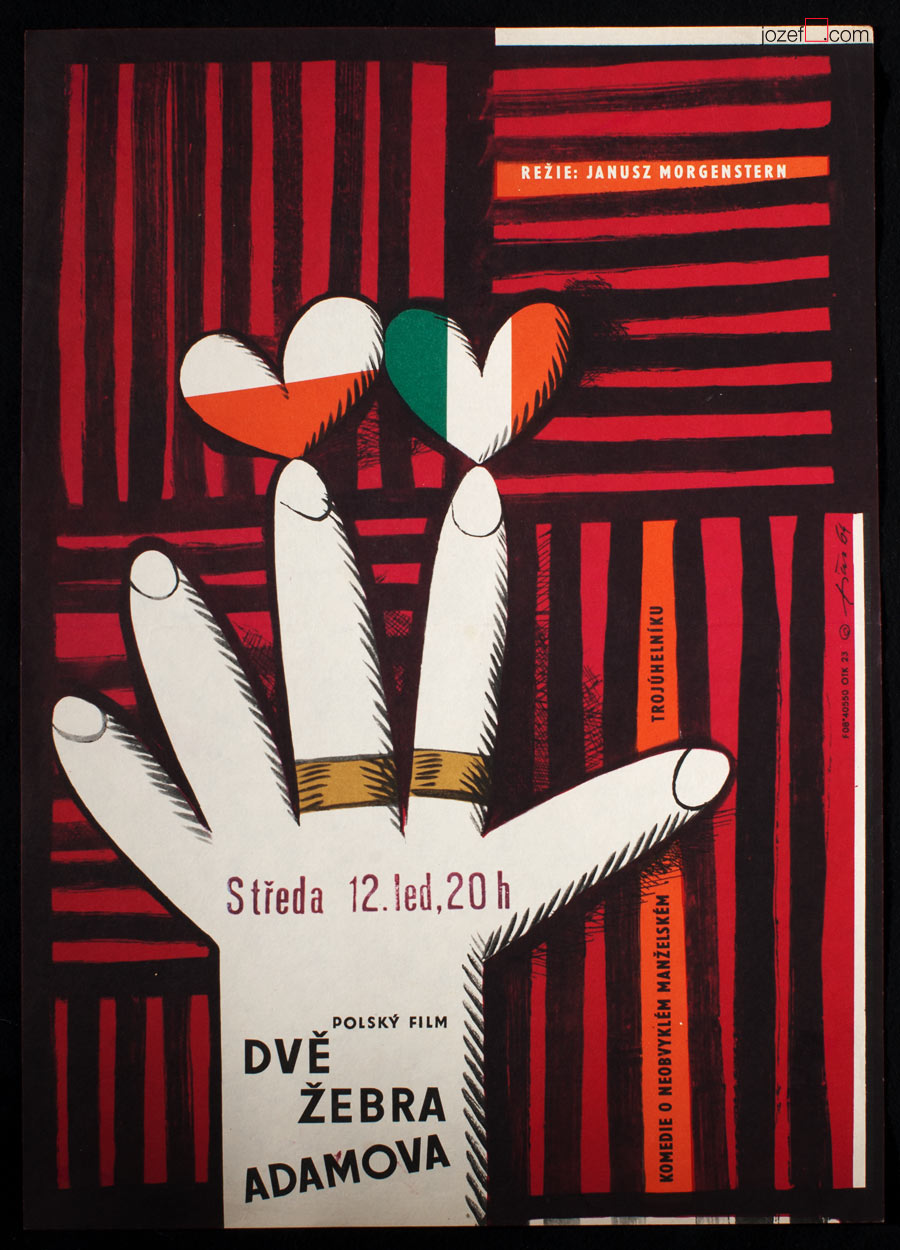

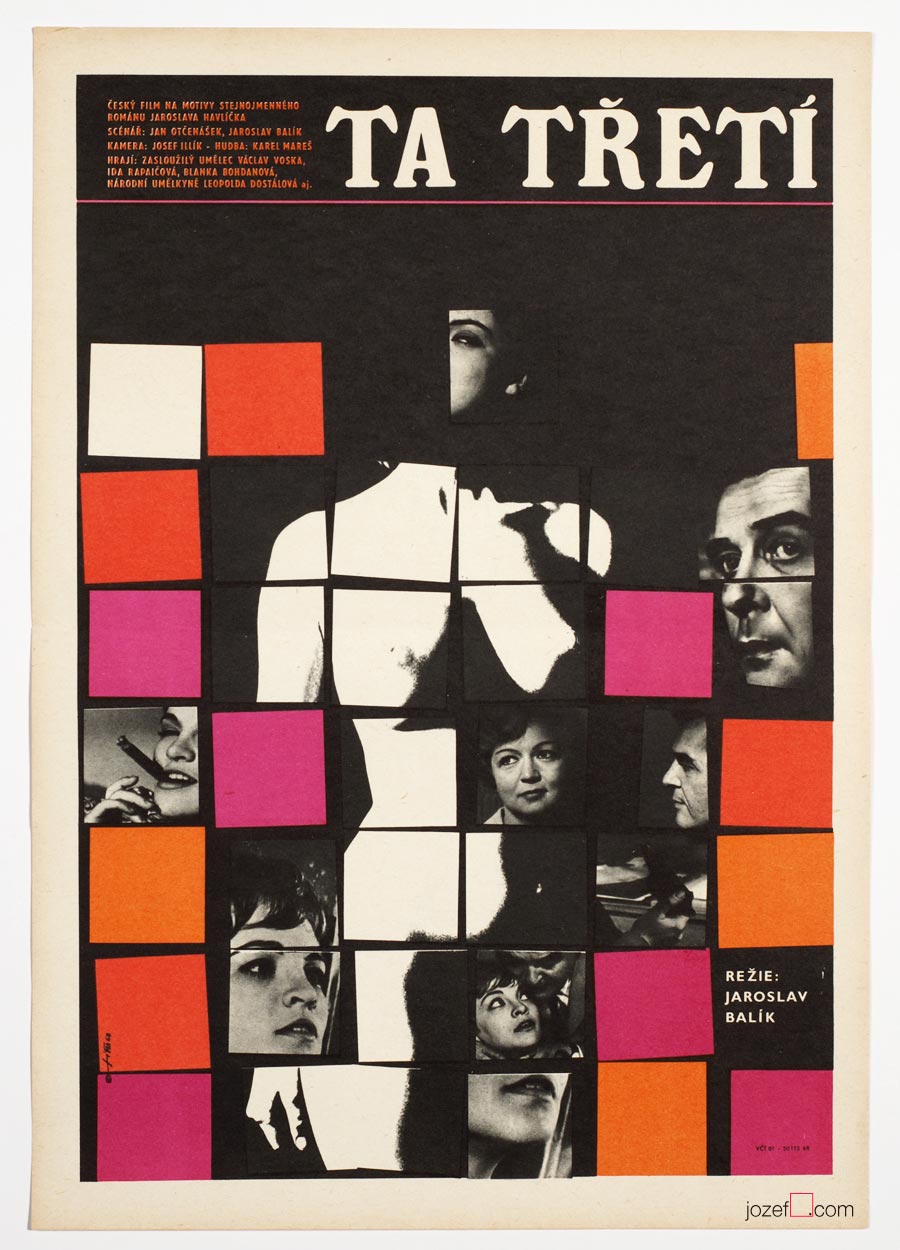

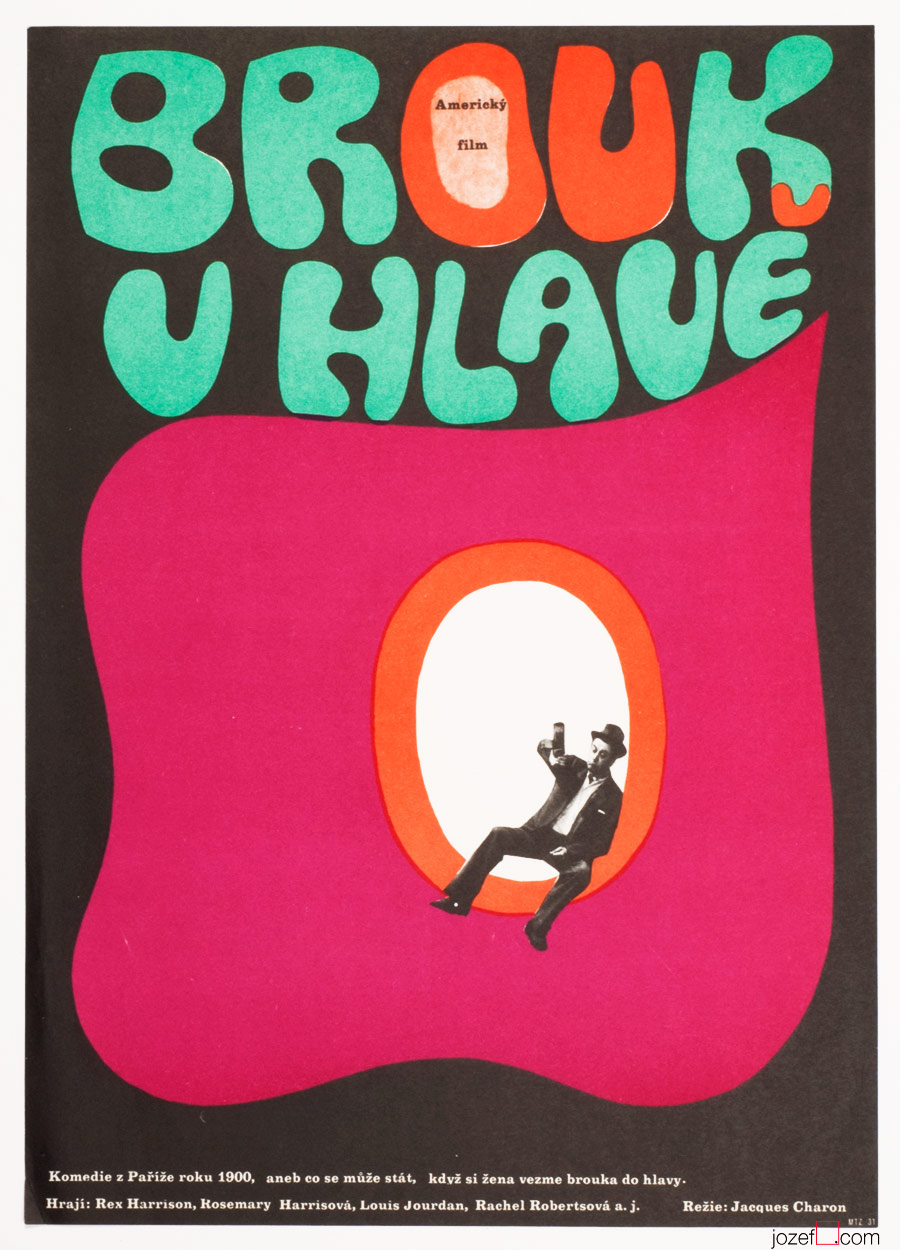

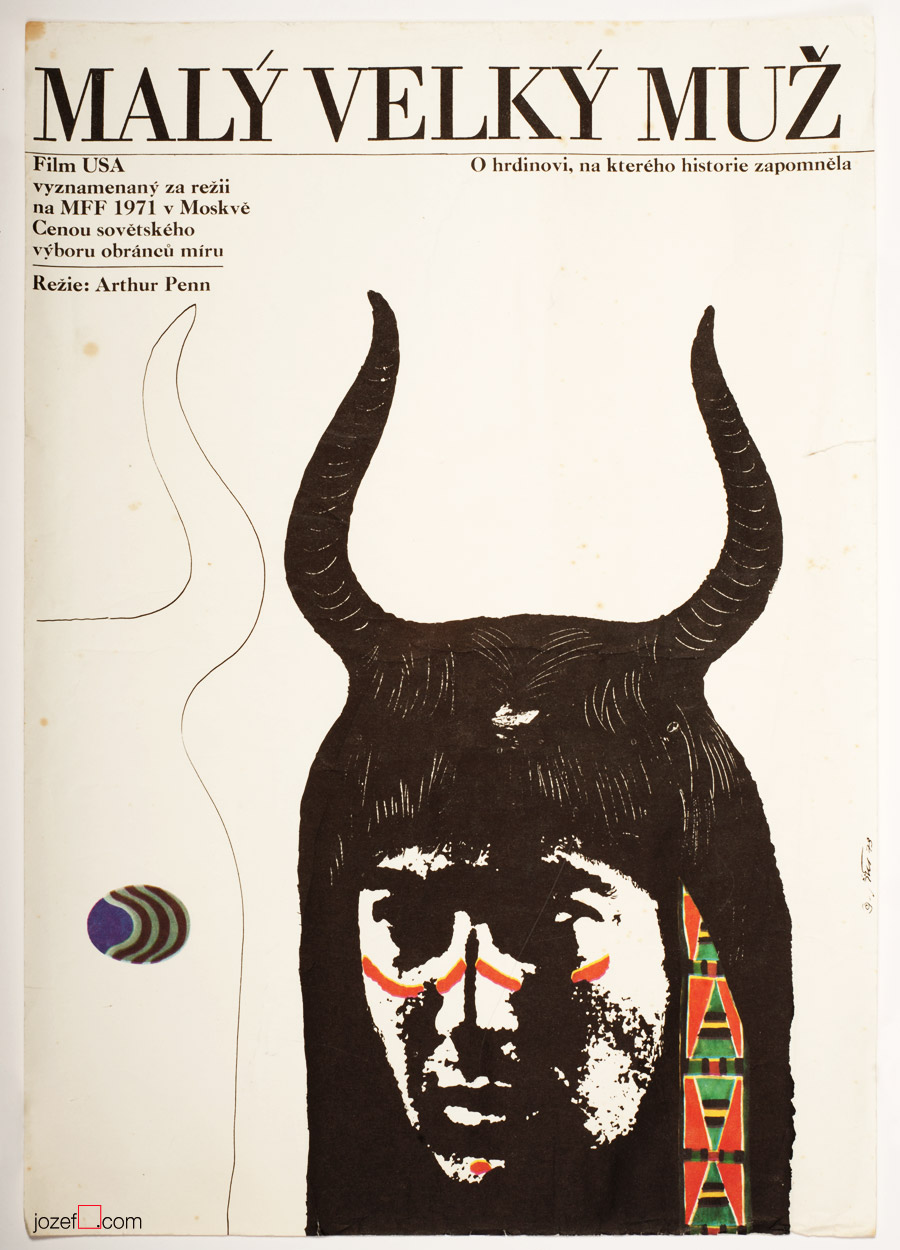

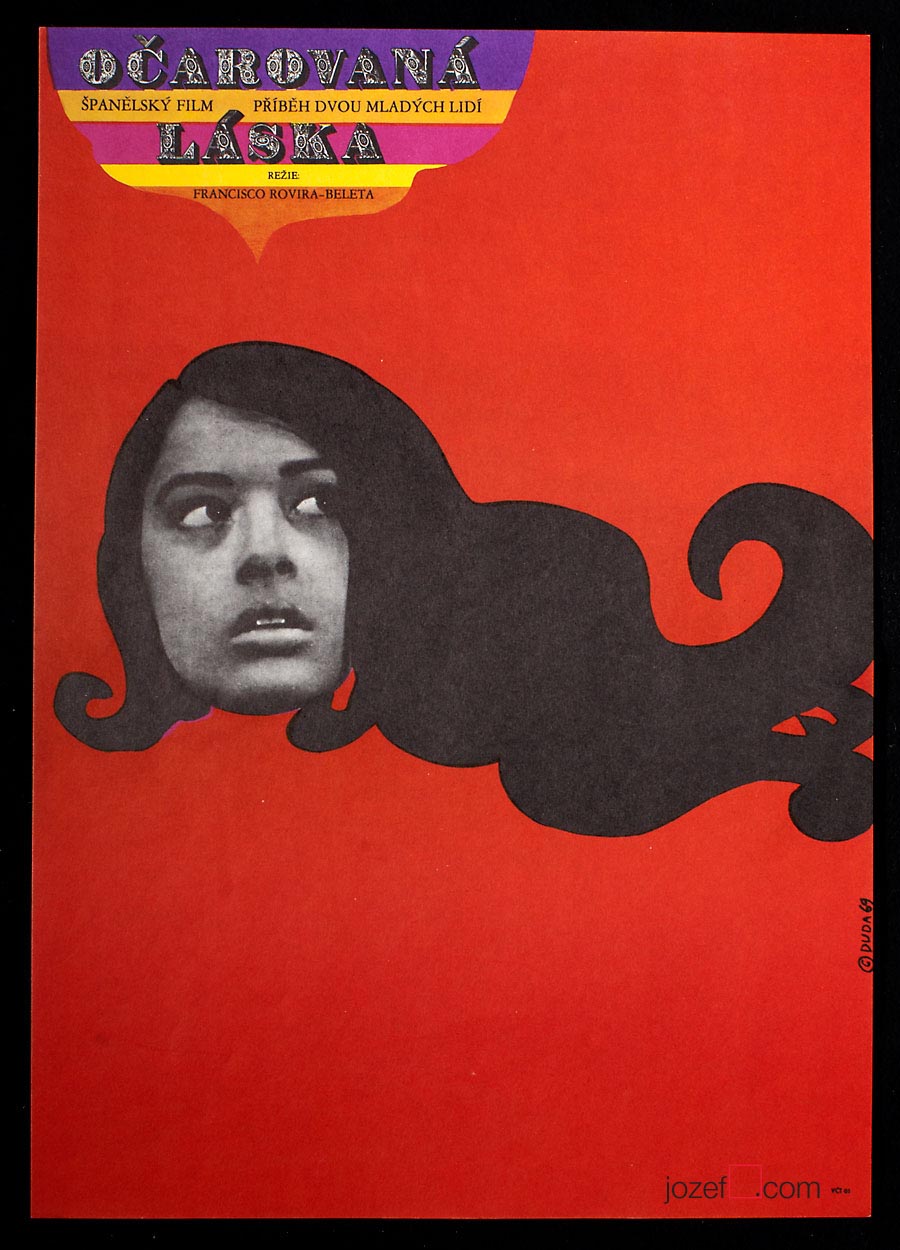

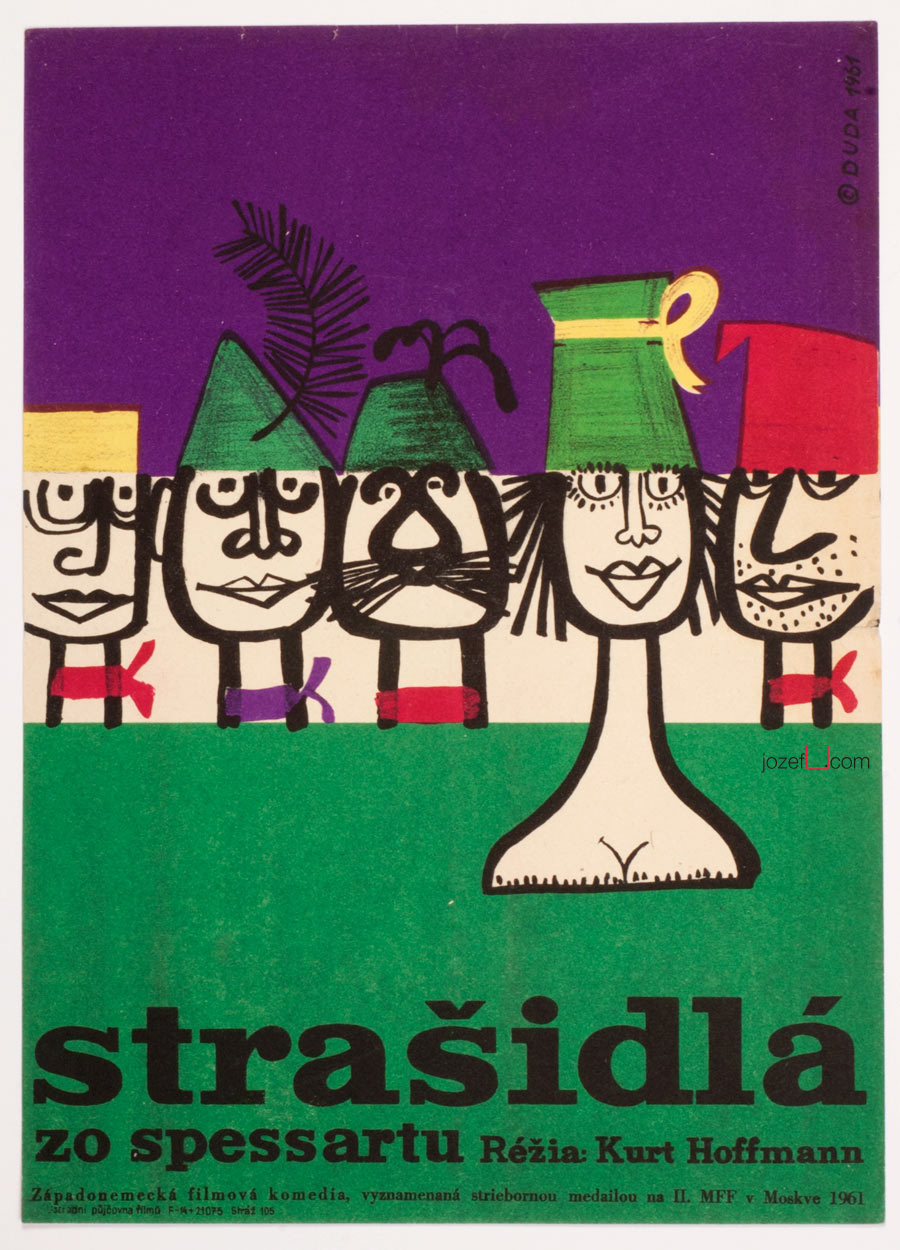

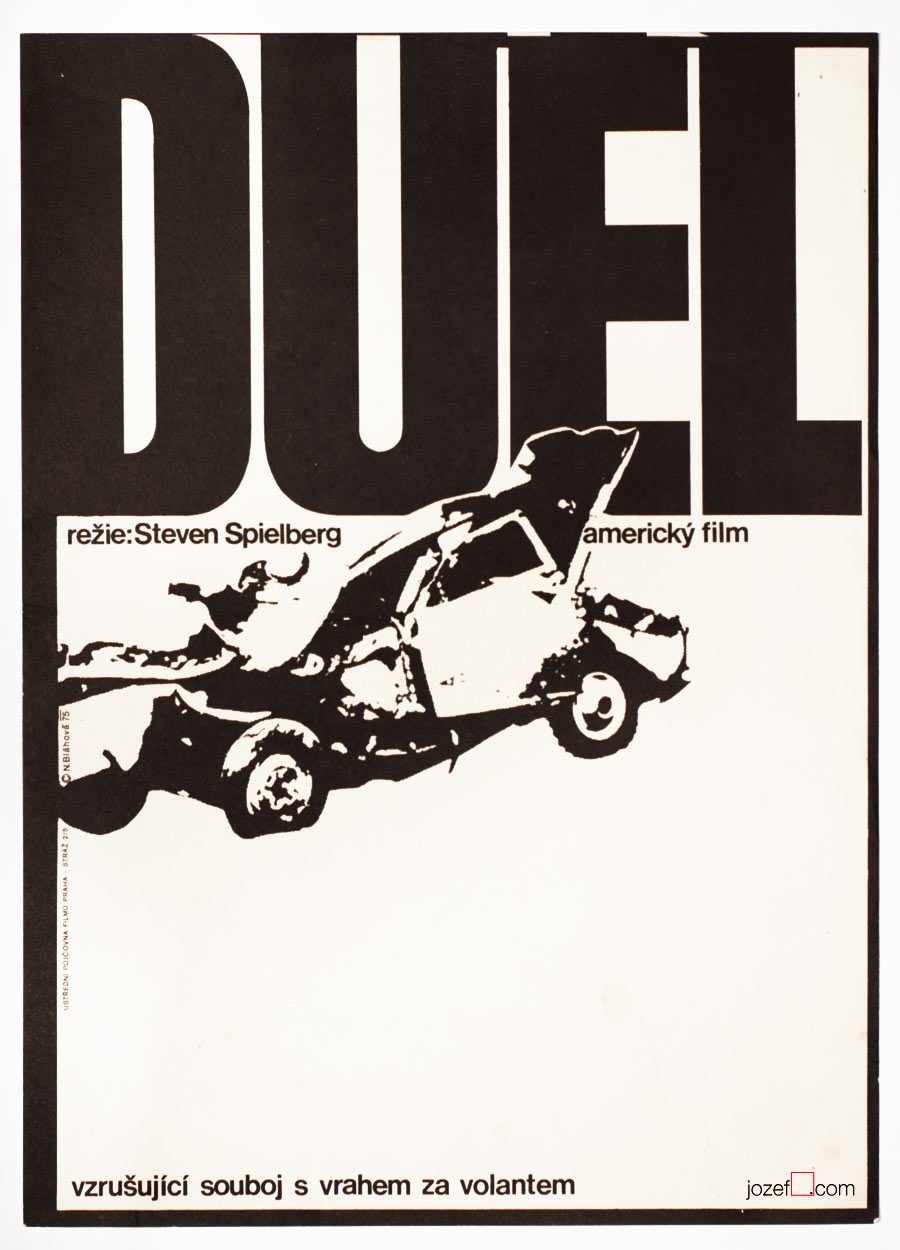

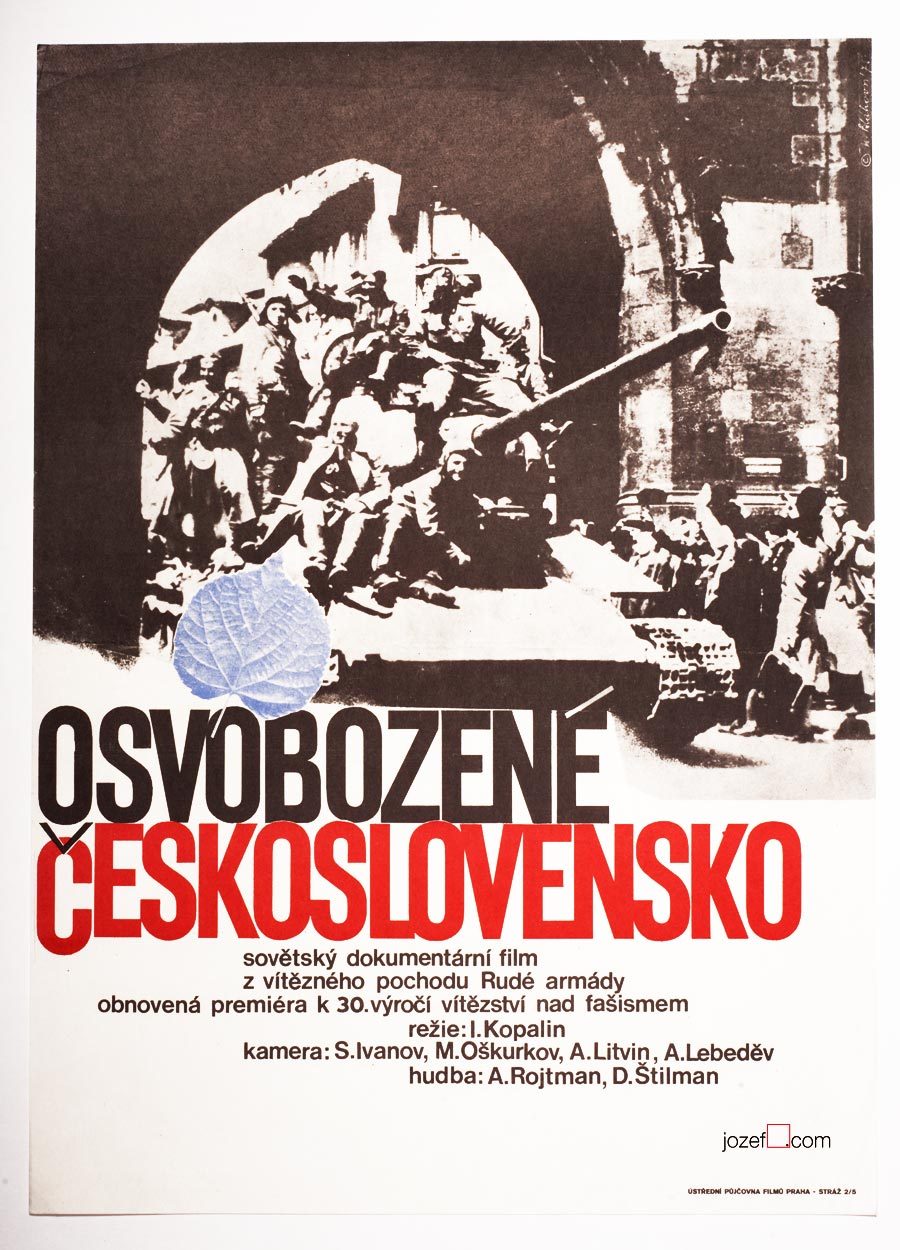

Poster Designs / Sixties – Adolf Born. The Story of Film Posters.

Film posters in history. Sixties poster designs.

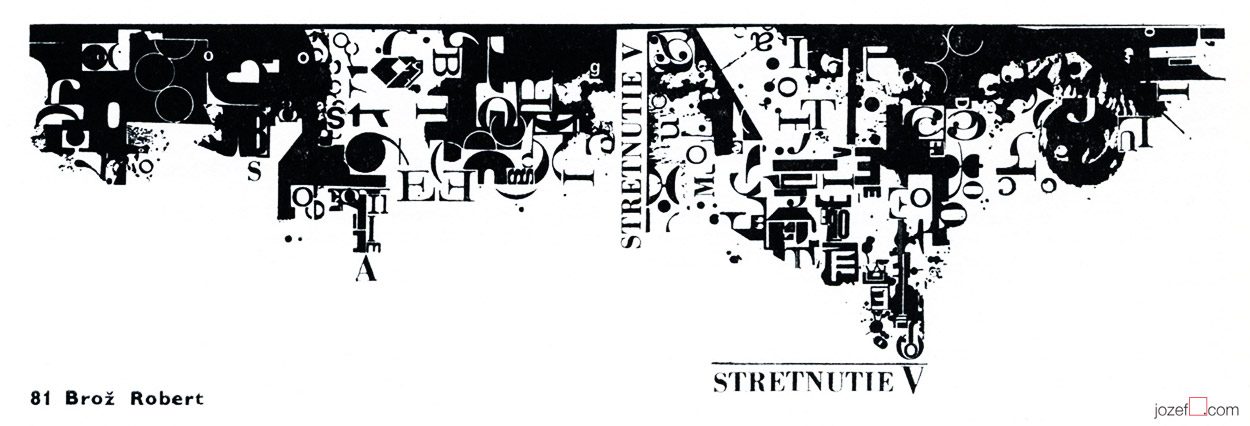

Poster Designer / Adolf Born

Painting / Stage Design / Illustration / Graphic Art / Caricature / Animation

***

- b. 12th of June 1930, České Velenice, Czech Republic

- lives and works in Prague, Czech Republic

Education:

- 1949−1950, Charles University, Prague (Faculty of Pedagogy / Art?)

- 1950−1953, Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague (Pelc Antonín)

- 1953−1955, Academy of Fine Arts, Prague (Pelc Antonín)

Awards:

- many, mostly for his animated films and book illustration (few shown bellow)

- 1974, caricaturist of the year, Montreal

- 1979, Golden Apple, Book Illustration Biennials, Bratislava

- 1985(?), Gold Medal, IBA, Leipzig

- 1988, Honorary Artist

Film posters designed: 19 (1959-1989)1

***

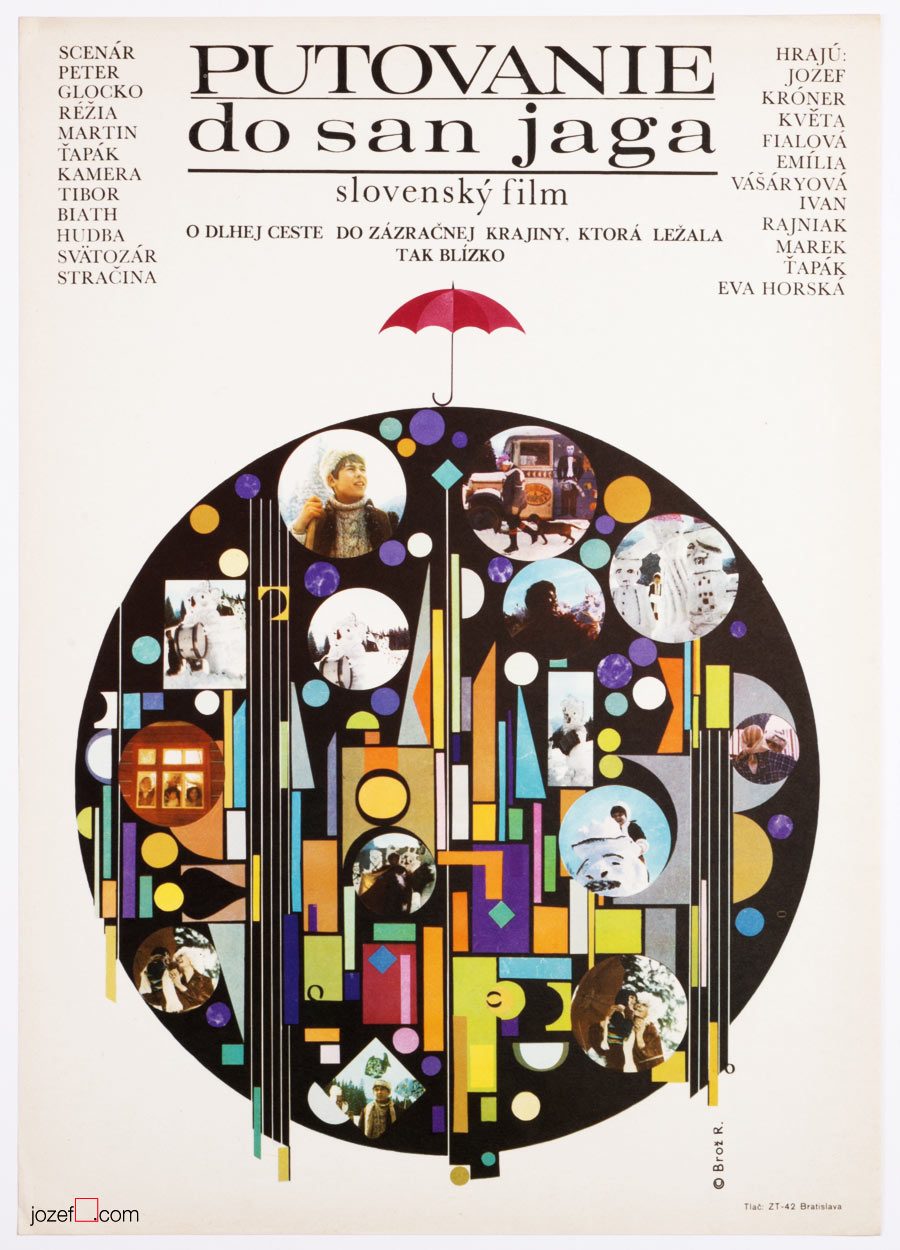

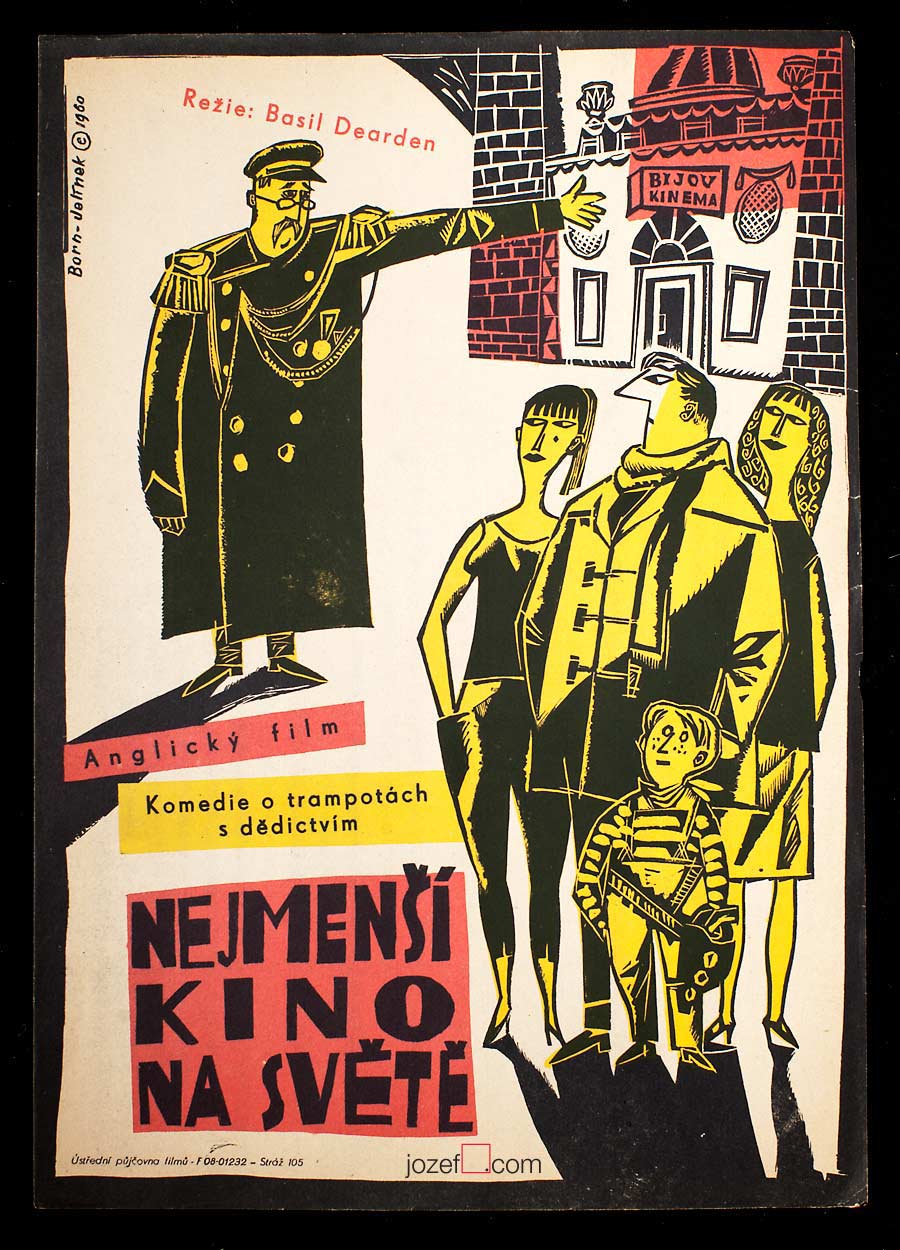

The Smallest Show on Earth – Adolf Born / Oldřich Jelínek, 1960.

The Smallest Show on Earth – Adolf Born / Oldřich Jelínek, 1960.

***

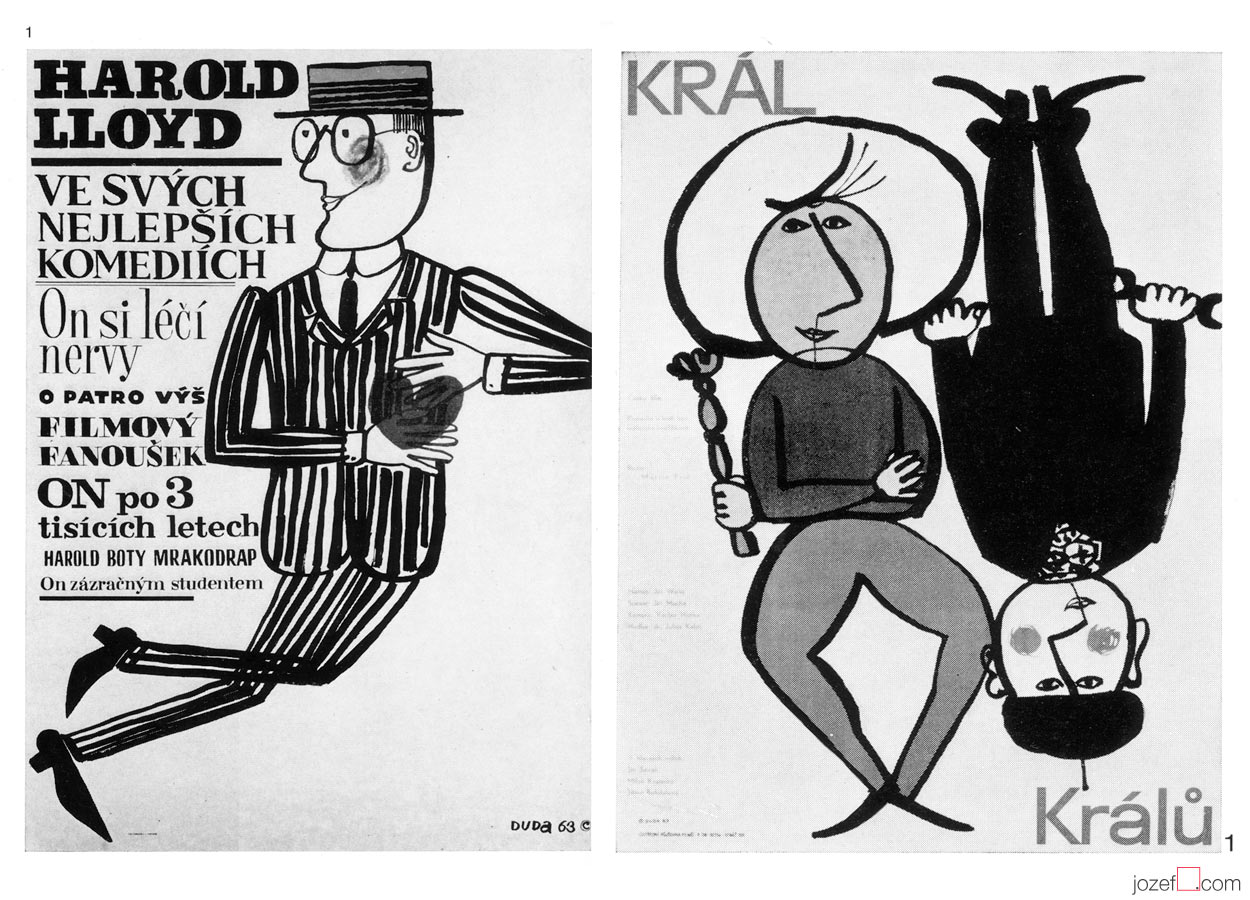

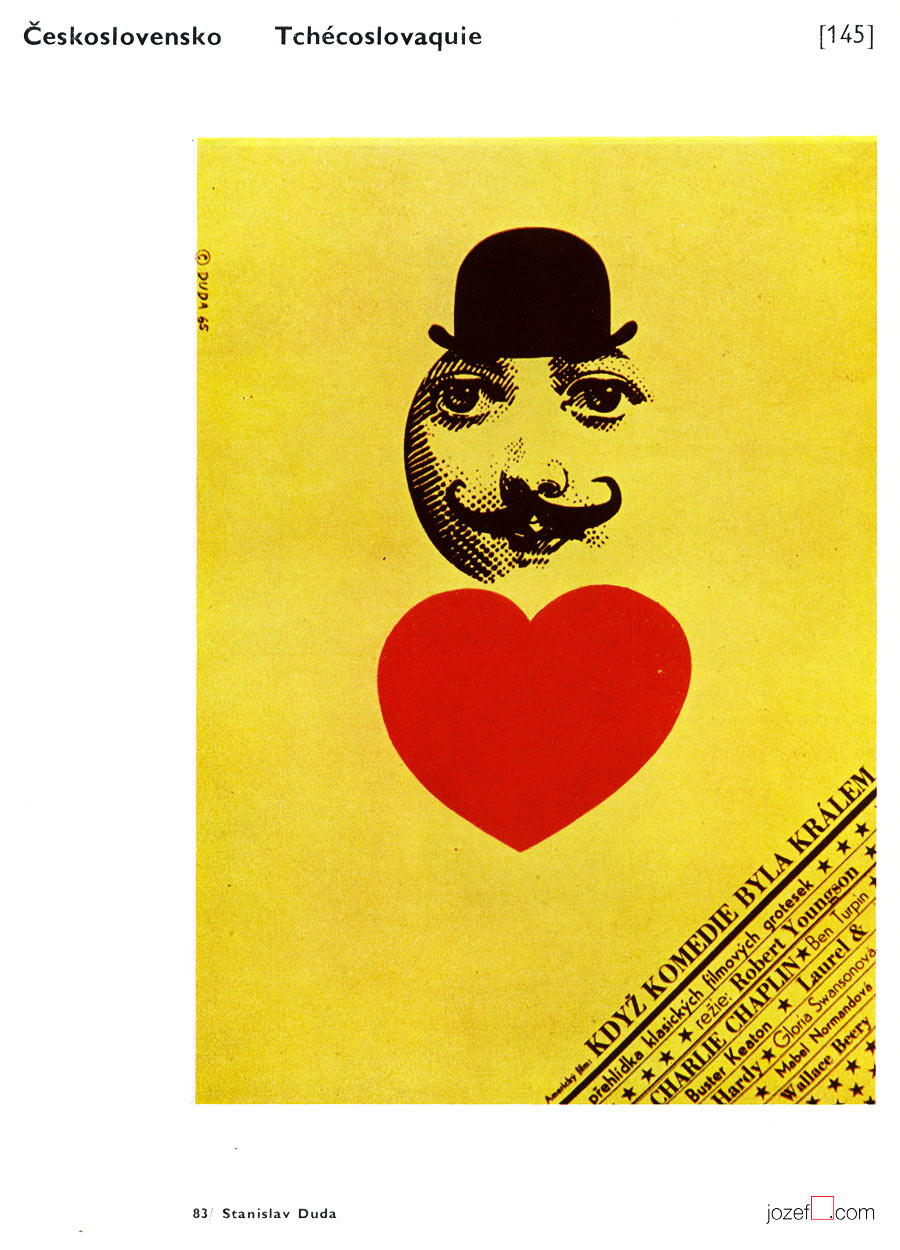

To meet with the fantastic world of Czech artist Adolf Born in former Czechoslovakia was not as complicated. One only had to get born there and the ticket for his show was lying in front of you. His visual presence was absolutely everywhere. Book illustrations and television programme was provided for the smallest audience and for those older ones there were magazines covered with his caricatures. He has also made the older population interested into watching animated films for the children.

Adolf Born’s work is well known also to international spectator. His book illustrations (over 400 books) and animated films (by the 1980 he produced 45 of them)2 visited many countries and have taken part in many exhibitions. Humorous depiction is very characteristic in his work. Adolf Born is here to make you smile.

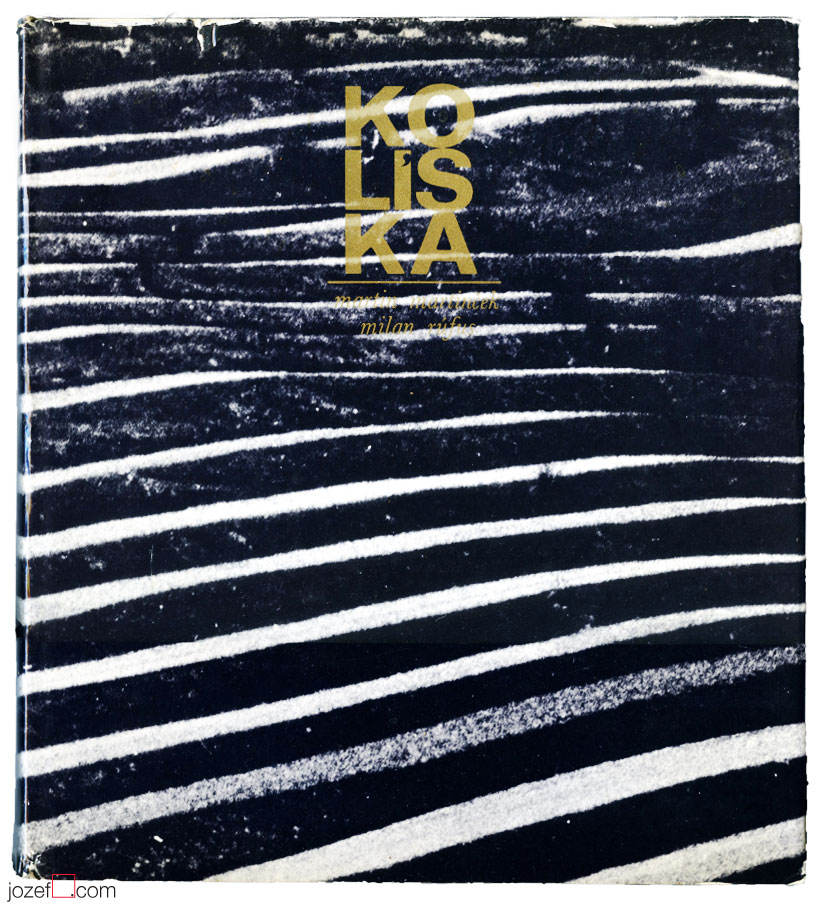

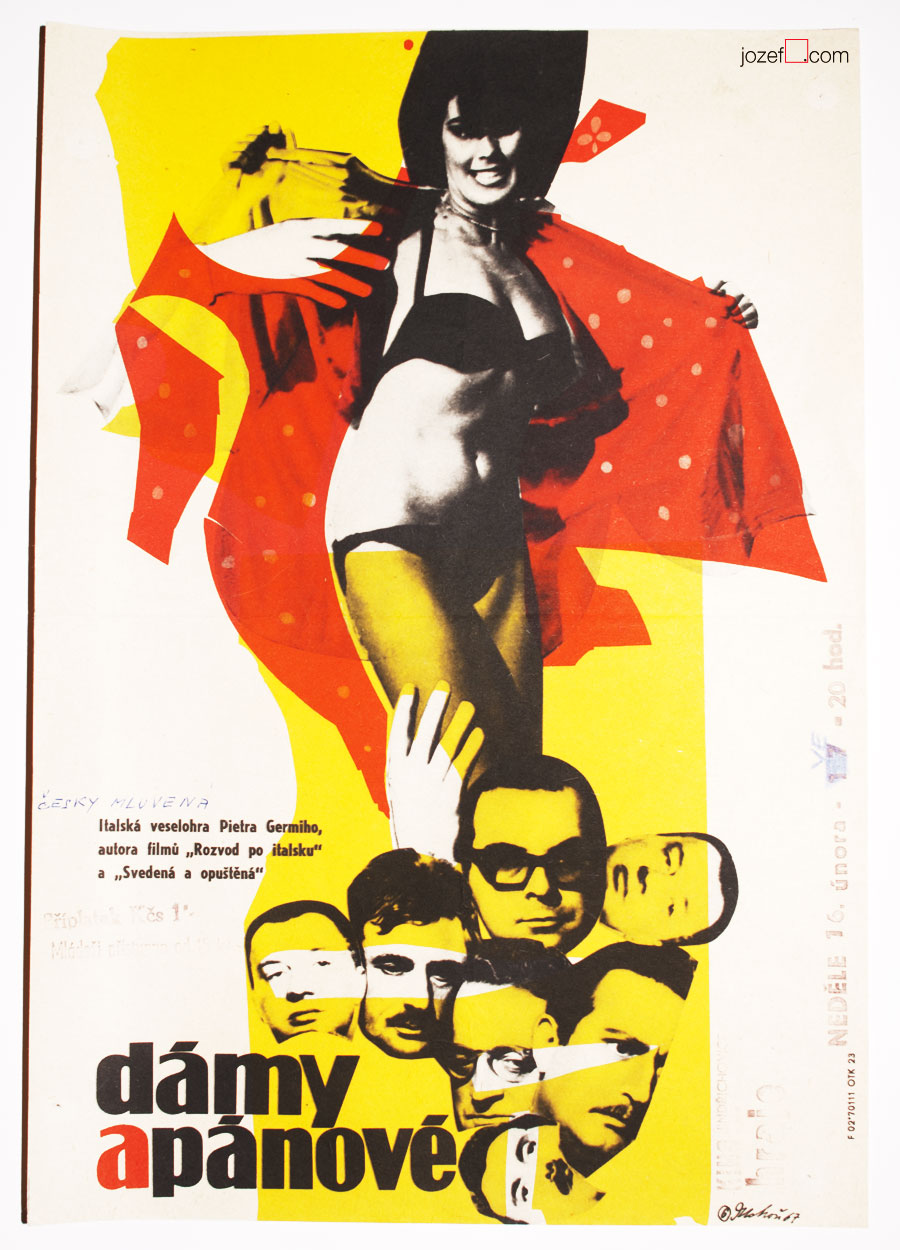

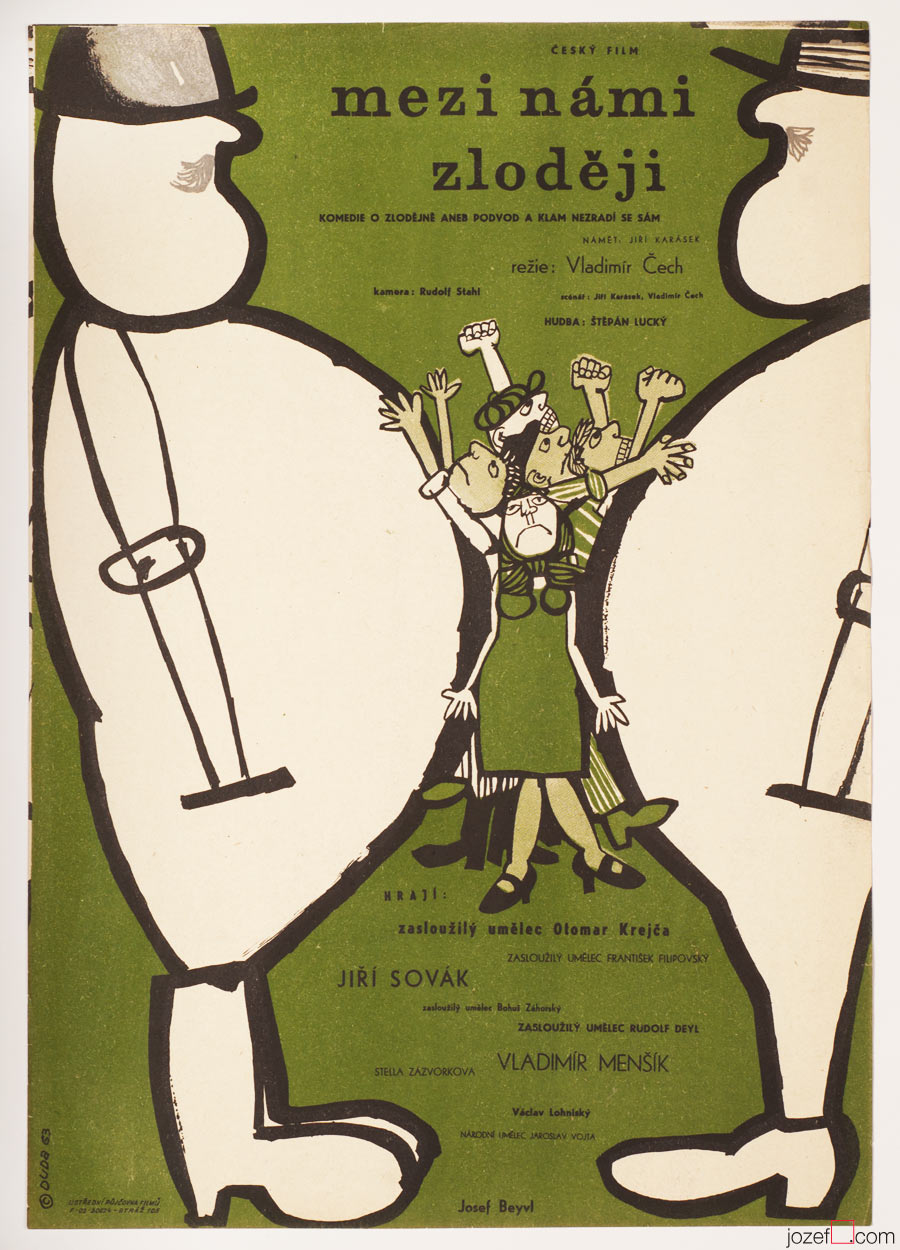

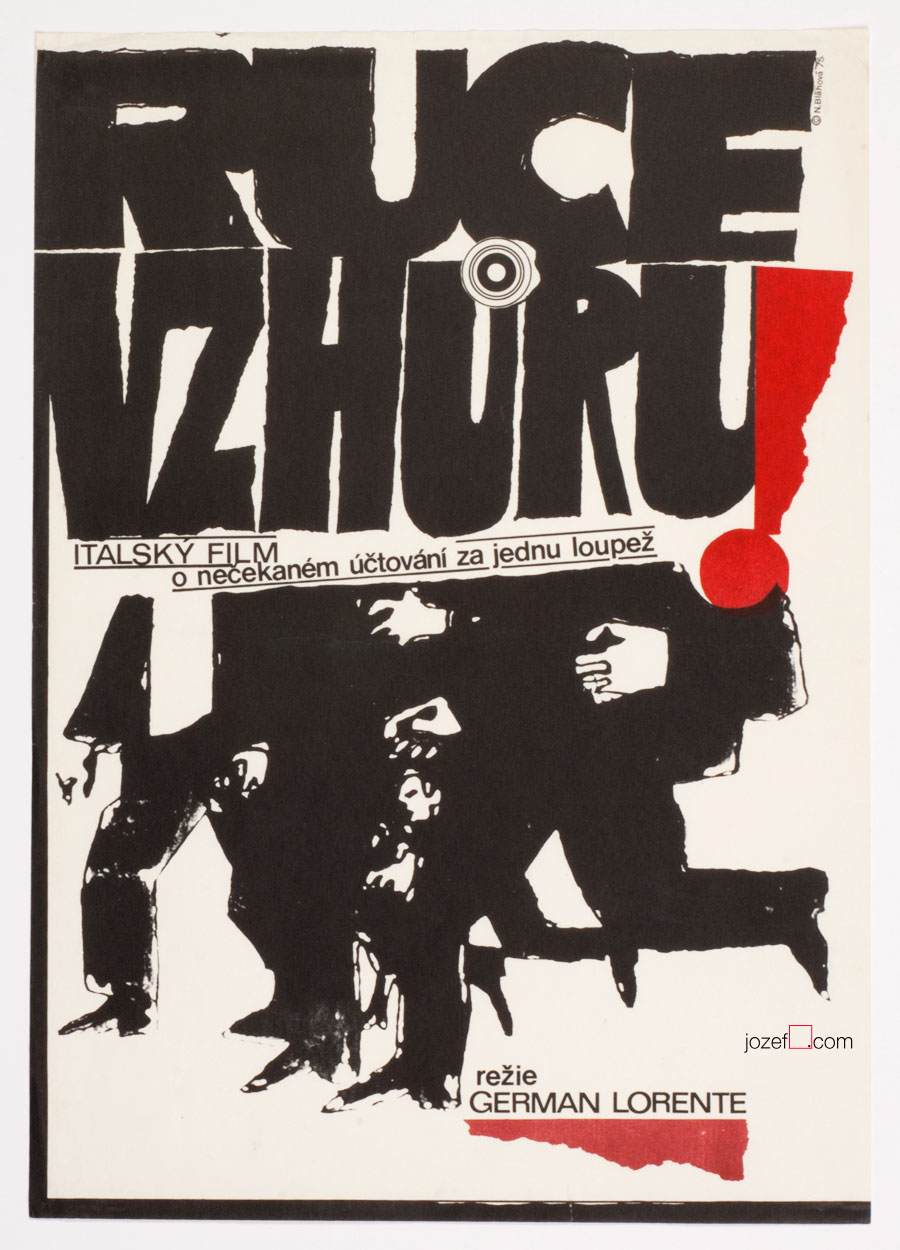

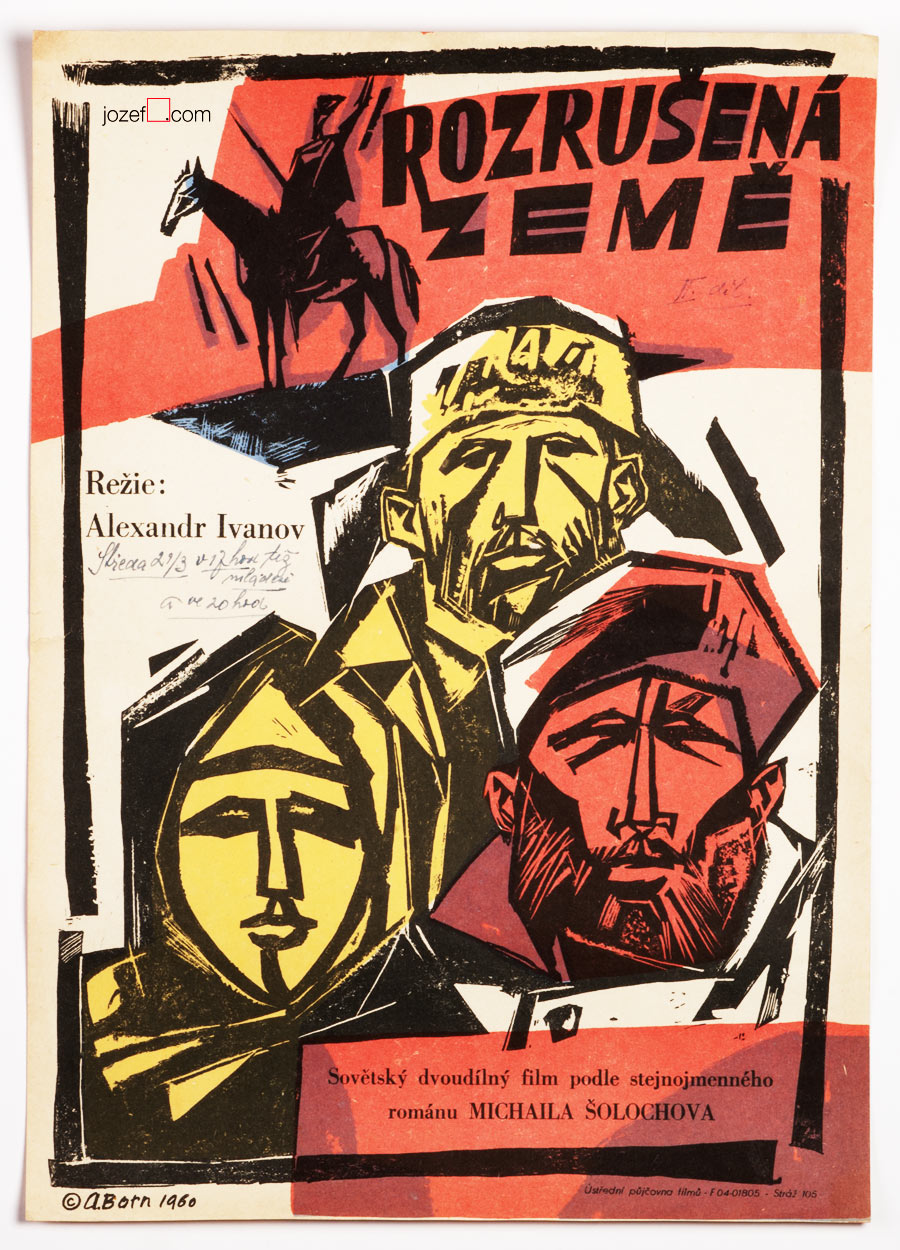

His film poster portfolio extends from early 1960s all the way to mid 1990s, with limited number designed. Adolf Born was preoccupied with other things. Film posters were possibly only other commission he was getting from the art union, where every illustrator/graphic had to be a member. Very few, but all very impressive. If the film poster was not made for the World War II film, it would definitely leave one with the grin on the face.

***

***

Note: this showcase is part of our ongoing article Film posters / Made in Czechoslovakia. The story of film posters.

Available posters by Adolf Born or other interesting film posters designed in Sixties.

***

Resources:

Literature:

- 1. Flashback / Czech and Slovak Film Posters 1959-1989, ed. Libor Gronský, Marek Perůtka, Michal Soukup, Olomouc Museum of Art, 2004. (p.45)

- 2. BIB, Bienále Ilustrácií / Biennale of Illustration ’79 ’81, Bratislava; Anna Horváthová, Mladé Letá, 1983 (p.60)

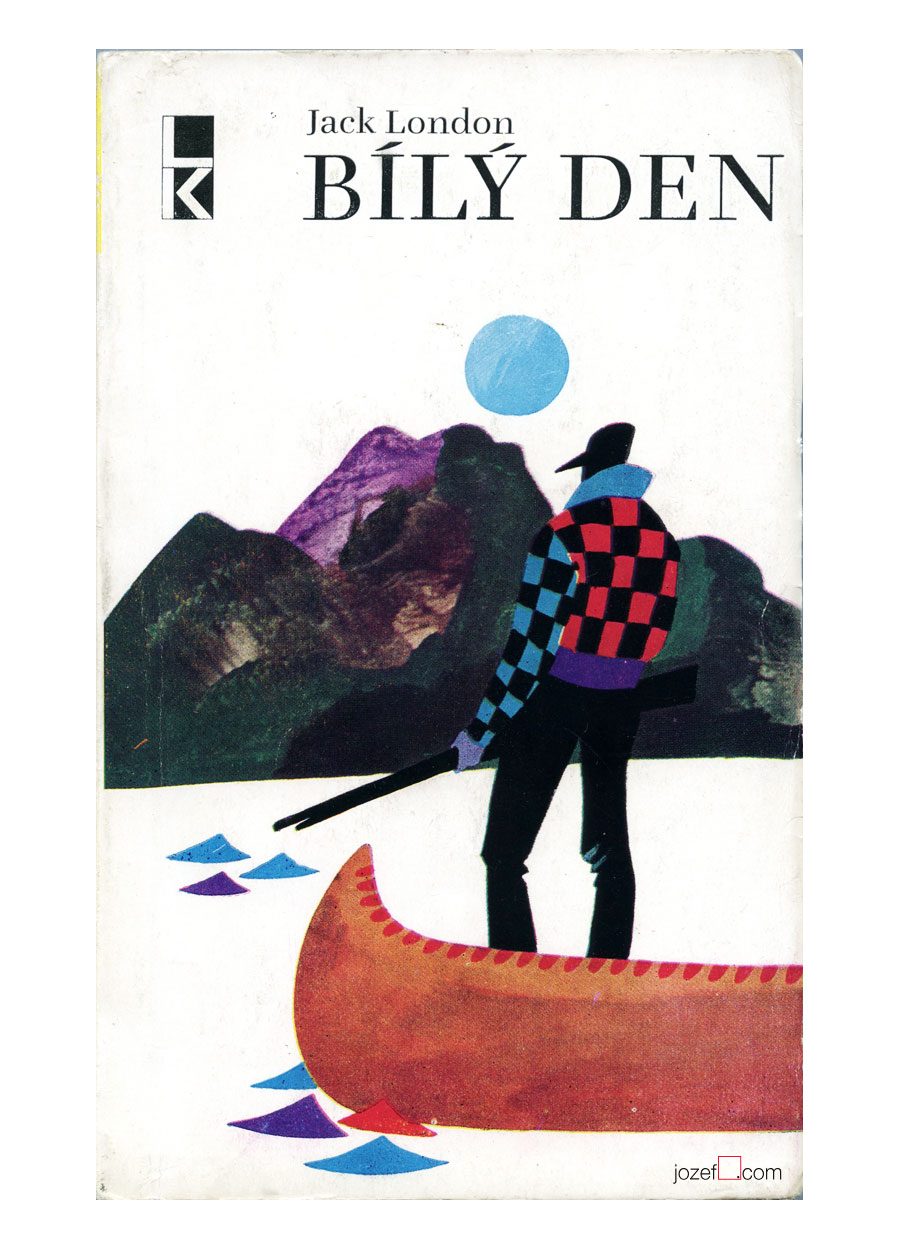

- 3. Burning Daylight / Jack London; Lidová knihovna, 1970

Online resources:

- abArt / Adolf Born

- Český Rozhlas / Czech Radio Broadcast (archive full of interviews with Adolf Born)

For shop and blog highlights, please SUBSCRIBE to our newsletter.